SCARY COOL SAD GOODBYE 34

At the time of his death, if he were on Jupiter, Elvis would've weighed 648 pounds.

“An American flag, hanging with the stripes vertical and the stars at the bottom left.”

— STANLEY BOOTH, ‘Furry’s Blues’

“I was all around the water tank, waiting for a train

Thousand miles away from home, I was sleeping in the rain

I walked up to the brakeman to give him a line of talk

He says if you got money, I’ll see that you don’t walk

I haven’t got a nickel, not a penny can I show

Said get off, get off, you railroad bum, and slammed that boxcar door.”

— JIMMIE RODGERS, ‘Waiting for a Train’

The train had left New Orleans mid-afternoon, nearly skimming the pink-brown bayou waters through mossy cypress groves where egrets napped. A small town’s strawberry festival butted against the tracks. Four sun-burnt men, conceivably hammered, led sixty Scouts aboard. (Passing their leader in the snack car, I inquired into their allegiances. “Future fascists of America,” the man hiccuped.) By 10:30 I’d stepped out of Memphis Central Station and onto the set of Mystery Train, caught in the same Arcade Restaurant neon as the Japanese rockabillies circa ‘89; except that the station was now a hotel whose lobby bar blasted Kaytranada, and the dingy hotel of the Jim Jarmusch film now a gift shop called Paper & Clay.

“If I were to catch the bus to Graceland, which way would that be heading?” I asked the gift shop’s blonde proprietor the next morning, having cleared fried eggs, bacon, grits, and a stack of sweet potato pancakes at the Arcade’s boomerang-print counter. “Oh, honey, I wouldn’t take the bus. It isn’t very… reliable,” she replied with some pity, counting out a ten, two fives and five singles when I asked for change for a twenty.

“I could throw a rock from my window and hit Elvis Presley’s house,” said the man on the corner, waiting for a crosstown bus that might not ever come. The man, who’d identified me as a Chicagoan from one tattoo or another, was short and stood at an obtuse angle; working a job in San Antonio, where once he’d had a wife, he had broken his back. We’d been waiting now 45 minutes for our second bus this morning. (“You get off when I tell you,” the first driver had ordered, then gunned it 65 mph, clunking hard over potholes.) “How long does it usually take?” I wondered. “Could be hours,” he replied. “And it’s even worse on Sundays.” He once had a disability card that gave him free Uber rides, but then they stole his wallet, and…

Anyway, he’d lived in Chicago once, too. Now he was old and he lived with his sister, a stone’s throw from Elvis’s house. “This place is crap,” the man spat. “In Texas you could get a job. I should’ve never came back here.” Like a boring miracle, the bus appeared.

Before long it was evident that all the riders of the crosstown bus headed south on Elvis Presley Boulevard were, aside from me, old pals, or something like it. Each new citizen of the bus was greeted by name, asked about their family; cheers erupted upon the embarking of a toothless man who shook everybody’s hand. “Well this bus is a party,” I remarked to my seatmate, a kind fellow harboring a bag of pork rinds. “Aw, that’s Twin! Everybody know Twin,” he explained, and poured half the pork skins into my purse. “You’re going to want a snack for later.” The windows framed William Eggleston scenes: liquor stores, barbecue restaurants, motels long since returned to nature. The man with the broken back tapped me on the shoulder. “Me and you get off here.”

“Elvis Presley’s house is that way,” he pointed across the street, then despite his back, outpaced me and was gone.

Each of the four sinks of Graceland’s women’s restroom is occupied by a glamorous retiree, fixing her hairdo with such care you’d think Elvis had personally extended the invitation to meet him here at noon. In line, I wonder what had brought these other people here, young families with bored children whose reference points I can’t fathom. (Patriotic duty?) “For most of the years of its existence, Memphis has lacked a clear identity in the minds of outsiders,” wrote the journalist Stanley Booth in 1998. “It was only with the deaths of Martin Luther King and Elvis Presley that the world came to have any sort of focus on what Memphis even partly signifies. Death is a good place to start.”

We get our tablets and our headsets and board the van that runs up Elvis’s driveway towards a house resembling, in Booth’s words, “an antebellum funeral parlor.” I steel myself for shlock overload — John Stamos narrates the audio tour — but crowding into the Presleys’ foyer, I feel, I don’t know… floored? It’s tiny, actually, the powder-white living room — a 1960s freeze-frame of a poor boy livin’ rich, and the scene in so many books I’ve read where people wait hours, doing nothing at all, for Elvis to descend the stairs and let things happen again. In a 1968 Esquire piece published before the comeback special, Booth wrote of this living room, where boys and girls “sprawled, nearly unconscious with boredom, over the long white couches, among the deep snowy drifts of rug.” And all of a sudden there’s Elvis, smiling but not speaking, dressed in all black like a movie cowboy, cradling in his arms a big model airplane, which they’ll watch him try over and over to start as the engine sputters and dies.

“Elvis stands, mops his brow (though of course he is not perspiring), takes a thin cigar from his shirt pocket and peels away the cellophane wrapping. When he puts the cigar between his teeth a wall of flame erupts before him. Momentarily startled, he peers into the blaze of matches and lighters offered by willing hands. With a nod he designates one of the crowd, who steps forward, shaking, ignites the cigar, and then, his moment of glory, of service to the King, at an end, he retires into anonymity. ‘Thank ya very much,’ says Elvis.

They begin to seem quite insane, the meek circle proffering worship and lights, the young ladies trembling under Cadillacs, the tourists outside, standing on the roofs of cars, waiting to be blessed by even a glimpse of this young god, this slightly plump idol, whose face grows more babyish with each passing year. But one exaggerates. They are not insane, only mistaken, believing their dumpling god to be Elvis Presley. He is not. One remembers — indeed, one could hardly forget — Elvis Presley.”

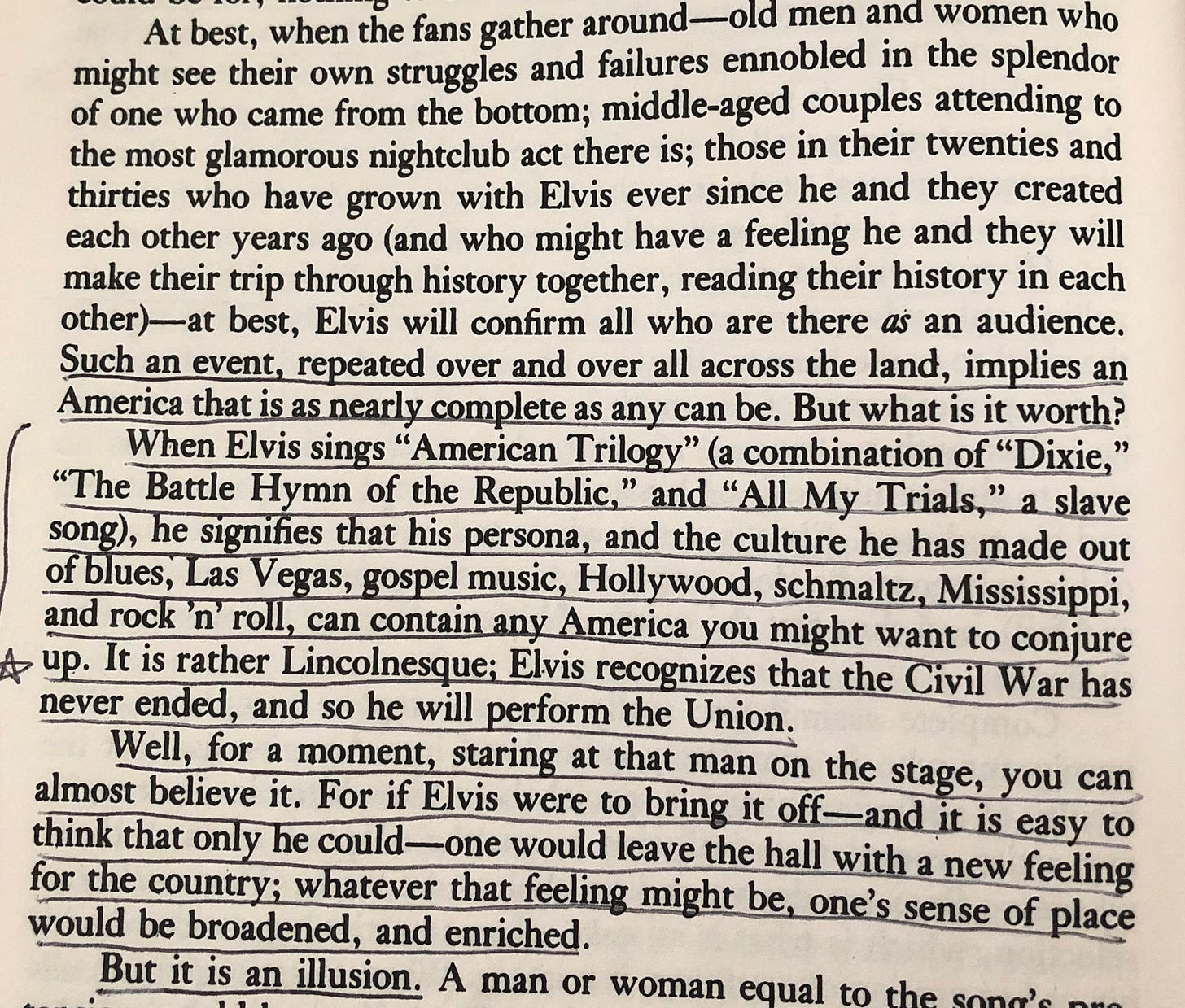

It offends me, almost, to read accounts of Elvis from this time, hearing from people who knew what he’d been, and what he would never be again, but who didn’t know how it would end. (People who hadn’t seen THIS!!) But those people were right. In my last post I quoted from Mystery Train, in which Greil Marcus presents six artists who delivered new versions of an America in which we are still trying to live; Robert Johnson is one of the first, and Elvis the last. “Beside Elvis, the other heroes of this book seem a little small-time. If they define different versions of America, Presley’s career almost has the scope to take America in,” Marcus writes. “The cultural range of his music has expanded to the point where it includes not only the hits of the day, but also patriotic recitals, pure country gospel, and really dirty blues; reviews of his concerts, by usually credible writers, sometimes resemble Biblical accounts of heavenly miracles. Elvis has emerged as a great artist, a great rocker, a great purveyor of shlock, a great heart throb, a great bore, a great symbol of potency, a great ham, a great nice person, and, yes, a great American.”

Marcus started writing Mystery Train in ‘72, finished it in ‘74 — not Elvis’s most grotesque era but surely not his proudest years, during which he performed “as the transcendental Sun King that Ralph Waldo Emerson only dreamed about.” Onstage in Vegas in his Superman cape, pantomiming the fact of his own existence, Elvis at last transcends his own talent. “It is as if there is nothing Elvis could do to overshadow a performance of his myth. And so he performs from a distance, laughing at his myth, throwing it away only to see it roar back and trap him once again.” Marcus goes on: “It is a sure sign that a culture has reached a dead end when it is no longer intrigued by its myths (when they lose their power to excite, amuse, and renew all who are a part of those myths — when those myths just bore the hell out of everyone); but Elvis has dissolved into a presentation of his myth, and so has his music.”

And what shape does the illusion take? “The last word of our mainstream; its last, most seductive trap: the illusion that the American dream has fulfilled itself.”

But inside the illusion is all the enchantment you could ask for — a Saturday night approached with the fire-and-brimstone intensity of a Baptist church revival, “a cosmic conspiracy against reality in favor of romance” (as the writer W. J. Cash described a certain disposition in The Mind of the South), the conspiracy to which rock ‘n’ roll gave form and made into tradition. “Why not trade pain and boredom for kicks and style? Why not make an escape from a way of life — the question trails off the last page of Huckleberry Finn — into a way of life?” Marcus asks. “How could an honest man be satisfied to live within the frontiers he was born to?”

Midway through the chapter there’s an awful footnote, a thought exercise from 1975: “It is perhaps 1990. Elvis is in his middle fifties now, still young, still beautiful.”

I didn’t listen to much of Elvis’s music in Memphis; somehow, it didn’t fit the mood. Instead, I wandered mostly to the songs of Furry Lewis, who some have called the very personification of the Beale Street blues. Born in 1893 to Mississippi sharecroppers, his family moved to Memphis, then the largest inland cotton market in the world. Furry went to school until fifth grade, then joined a traveling medicine show, where he was sort of a comedian; he got fond of hopping freight trains, seeing where they’d take him. “That’s how I lost my leg,” he explained decades later. “Goin’ down a grade outside Du Quoin, Illinois, I caught my foot in a coupling. They took me to a hospital in Carbondale. I could look right out my window and see the ice-cream factory.”

That’s from a wonderful Playboy story from 1970, written by the same Stanley Booth as the Elvis piece above, and entitled “Furry’s Blues.” Before that, though, I should tell you about Booth, one of a scarce few who give music writers a good name. Booth was raised on a turpentine camp in South Georgia, whose swamplands had been given the Seminole name for the Land of the Trembling Earth. Later he moved to Memphis, still very much segregated, where he worked as a karate instructor and for the Tennessee Welfare Department before finding himself, by accident, a journalist. (His Esquire account of life at Graceland was the first ‘serious’ magazine coverage of Elvis at the time; in his stay at the Presley’s he also managed to overdose on Darvon, a narcotic that’s been banned since.) Booth watched Otis Redding record “(Sittin’ On) the Dock of the Bay” two days before his plane crash, drank bourbon for breakfast with B.B. King, got deep into Keith Richards’ medicine bag while touring with the Stones, picked up seven felonies for, well, long story, broke his back falling off a waterfall on acid, and went into hiding in the mountains for a spell. (He’s alive, mind you, at 81.) My favorite thing he did, though, was profile Furry Lewis, who would become his lifelong friend.

“By now there must be in the world a million guitar virtuosos; but there are very few real blues players. The reason for this is that the blues — not the form, but the blues — demands such dedication. This dedication lies beyond technique; it makes being a blues player something like being a priest. Virtuosity in playing blues licks is like virtuosity in celebrating the Mass, it is empty, it means nothing. Skill —competence — is a necessity, but a true blues player's virtue lies in his acceptance of his life, a life for which he is only partly responsible.” —STANLEY BOOTH

Watch how, at 0:14 in the video above, Furry flips the song’s direction, how he does it again at 0:31; the way his hands are moving appears almost random, though the music doesn’t sound it, improvising subtly towards the mood that he is building. A protegé of W.C. Handy, “the Father of the Blues,” Furry was beloved on Beale Street in its heyday, “where somebody was killed every Saturday night and born every Sunday” (his words); he played riverboats and gambling houses up and down the Mississippi, and even cut some records for Vocalion in Chicago. Then the Depression came and Beale Street changed, and lots of people left, but Furry stayed. He took a job in 1923 with the Memphis sanitation department, sweeping the streets five mornings a week before the sun came up. And when Booth finds him 45 years later, that’s what he’s doing still.

“The sky is black. The alley is quiet, the apartments dark. A morning-glory vine hanging from a guy wire stirs, like a heavy curtain, in the cool morning breeze. Cars in the cross alley are covered with a silver glaze of dew. A cat flashes between shadows.

Behind Bertha’s Beauty Nook, under a large, pale-leafed elm, there are 12 garbage cans and two carts. Furry lifts one of the cans onto a cart, rolls the cart out into the street and, taking the wide broom from its slot, begins to sweep the gutter. A large woman with her head tied in a kerchief, wearing a purple wrapper and gold house slippers, passes by on the sidewalk. Furry tells her good morning and she nods hello.

When he has swept back to Vance, Furry leaves the trash in a pile at the corner and pushes the cart, with its empty can, to Beale Street. The sky is gray. The stiff brass figure of W. C. Handy stands, one foot slightly forward, the bell of his horn pointing down, under the manicured trees of his deserted park. The gutter is thick with debris: empty wine bottles, torn racing forms from the West Memphis dog track, flattened cigarette packs, scraps of paper and one small die, white with black spots, which Furry puts into his pocket. An old bus, on the back of which is written, in yellow paint, LET NOT YOUR HEART BE TROUBLED, rumbles past: it is full of cotton choppers. Their dark, solemn faces peer out the grimy windows. The bottles clink at the end of Furry’s broom. In a room above the Club Handy, two men are standing at an open window, looking down at the street. One of them is smoking; the glowing end of his cigarette can be seen in the darkness. On the door to the club, there is a handbill: BLUES SPECTACULAR, CITY AUDITORIUM: JIMMY REED, JOHN LEE HOOKER, HOWLIN’ WOLF.

When Furry has cleaned the rest of the block, the garbage can is full and he goes back to Bertha’s for another. The other cart is gone and there is a black Buick parked at the curb. Furry wheels to the corner and picks up the mound of trash he left there. A city bus rolls past; the driver gives a greeting honk and Furry waves. He crosses the street and begins sweeping in front of the Sanitary Bedding Company. A woman’s high-heeled shoe is lying on the sidewalk. Furry throws it into the can. ‘First one-legged woman I see, I’ll give her that,’ he says and, for the first time that day, he smiles.”

Furry had a second act in the ‘70s; he opened for the Stones in Memphis, played a part in a Burt Reynolds movie, even appeared on the Johnny Carson show where, to the question of why he was single, he replied, “Why in the hell do I need a wife when the man next door got one?” But if you wanted him to play, you would first have to visit the pawn shop down the street, where he’d hock his guitar for drinking money. Once, Joni Mitchell came to Furry’s house and interviewed him, and later wrote a song about it — “Furry Sings the Blues” — where she sings of a babbling, drunk old musician propped up in his bed with his peg leg removed, “down and out in Memphis Tennessee.” Furry hated that song. “She wanted to hear ‘bout the old days, said it was for her own personal self, and I told it to her like it was, gave her straight oil from the can,” he told a reporter in ‘77. “But then she goes and puts it all down on a record, using my name and not giving me nothing!” (Joni’s manager responded: “She really enjoyed meeting him, and wrote about her impressions of the meeting. He did tell her that he didn't like her, but we can't pay him royalties for that.”) “Now I know I ain't a star,” Furry went on, winking. “But I sure might be a moon.”

Some Furry Lewis songs are funny, with their train-hopping sexcapades, and others are terribly sad. (“My mother’s dead,” goes one of them, “my father just as well to be. Ain’t got nobody to say one kind word for me.”) My favorite of his songs is both. “Now, when you’re gone, I won’t feel bad,” he sings on “Farewell I’m Growing Old,” sounding jaunty enough while strumming a more complicated feeling. “I never miss those things I never had… Now let the git-tar sing!” he cries in his showman’s voice. “Gittar talks more than I do… Gittar must be drunk.” Then the gittar finishes Furry’s thoughts for him, and you understand just what he means.

For more SCARY COOL SAD GOODBYE on the topic of Elvis, you may click here.

For the previous installment of SCARY COOL SAD GOODBYE’s Amtrak chronicles, try here.