“Please, please let us all have more fantastic memories and write as well as we can of them.”

— MARK BERLIN

I was feeling kinda down and I needed something FUN, with a caveat: it needed also to be true. Look, we love Eve Babitz here,* I just wish she wouldn’t lie, going around swooning like she’d never spent the afternoon at the dentist or DMV. (You know I don’t mean that. I’m going through some things.) In any case, I wanted jacaranda and bougainvillea, enchiladas and oysters, jazz and flamenco, tanned soulful men with noblesse oblige — and the rest of it too, the sorrow and fear, the stuff that Miss Eve always kept out of frame. There’s only one thing for that sort of mood: the stories of Lucia Berlin.

I thought I’d read them all, which isn’t hard — two new collections, then older ones with different combinations of the same stories. (If you like this newsletter, A Manual for Cleaning Women is a must.) But I’d missed one: Welcome Home, which re-tells some of these stories, only this time as a memoir beginning 1936 in an Alaskan mining camp and ending somewhere near the border of Chiapas 30 years later. Berlin died in 2004 amidst writing the thing, hence the sudden ending, trailing off mid-sentence on the road to Guatemala, third husband shivering from withdrawal in the shotgun seat of a VW van. For 70 pages prior, she breezes through two divorces, the births of three sons, and 20 of the 33 homes she later lists in “The Trouble with All the Houses I’ve Lived In.” (“Oaxaca, Mexico—Herd of goats next door. Mildew. Struck by lightning on Monte Albán... White House, Corrales, New Mexico—Pump broke, well went dry, wiring blew, chickens died, rabbits died, termites, goat broke leg. Shot her... Griegos Road, Albuquerque, New Mexico—I burned it down.”) Only once in her memoir does she mention writing at all.

* I did recently learn that my three great formative influences (Eve Babitz, Dennis Rodman, and my mother) share a birthday, May 13.

Lucia Berlin wrote with great feminine wiles, starting a story like, “Wait. Let me explain...” Or, “I like working in Emergency — you meet men there, anyway. Real men, heroes. Firemen and jockeys.” In her stories, often brutal, she was funny and warm, up for adventure, never a victim. I believe she was quite cunning, the way she kept things moving so as never to be boring (second only to lying as a writer’s greatest sin). But in spite of the immense control she obviously exercised, her writing sparks with life and rings with truth. Watch what happens in the course of four short paragraphs from a chapter set in Albuquerque 1956, just after her first marriage to a sculptor who... well, look:

“Paul chose all the furniture in the house. Black and white and earth colors. Java temple birds in a black cage had the faintest touch of pink on their throats. Mondrians on the wall, pewter Nambé ware ashtrays, Acoma and Santo Domingo pottery, a fine Navajo rug. Our dishes were black, our stainless a daring modern style. The forks had only two tines, so it was difficult to eat spaghetti.

We had our first child to keep Paul from being drafted. I accidentally got pregnant again when Mark was only a few months old. Paul said the only solution was for him to leave, so he did. He had a grant, a patron, a villa and foundry in Florence, and a new straight-nosed girlfriend.

The morning he left, the first thing I did was to give the birds to an old lady across the street. I took down the Mondrians, put up my sunflowers and an Elvis poster, tossed a gaudy Mexican blanket over the ecru couch. I put on pink lipstick, braided my hair into pigtails.

I was smoking cigarettes borrowed from next door, my bare feet were up on the table. The dishes were unwashed. Mark crawled around in a soaking-wet diaper, pulling pans out of the cupboard. Joe Turner was singing the blues on the hi-fi when Paul came in the door. He had only been gone for about twenty minutes when his car broke down. He didn’t think it was funny at all. We didn’t see him again for sixteen years.”

The forks had only two tines...

Here’s another one, a whole story condensed onto a page. This, too, in Albuquerque but earlier, at college, describing Berlin’s first love with a 30-year old Mexican American sportswriter in school on the G.I. bill:

“Don’t show your feelings. Don’t cry. Don’t let anyone know you,” Berlin once described her sensibility in a letter to a friend. True, her writing did not allow even a moment of self-pity. (“We laughed about the first precept of Buddhism: life is suffering,” wrote her first son, Mark Berlin, a great writer himself, in a eulogy, later the foreword to her second posthumous story collection, Evening in Paradise. “And the Mexican attitude that life is cheap, but it sure can be fun.”) As for feelings*, I’m not sure. Though her work never approached sentimentality, not even close, you get the idea that Berlin’s life was wildly romantic and terribly difficult, that she dealt with its chaos with grace and humor, yes, but also escapism, avoidance. In the many years that followed the memoir’s abrupt end, Berlin raised her four sons alone and “obliterated her health on Jim Beam over decades” — so wrote Dave Cullen, her former student, after A Manual for Cleaning Women became an NYT best-seller 11 years after her death. It’s a wonderful remembrance, mostly for the principles he picked up from Berlin and passes on to us. “Write what you see, not what you want to see, Lucia said. Or what you assume. ‘Look. Really look.’”

* I see now, the difference — “feelings” vs. “feeling.” First to be avoided. Second one’s the thing.

A jazz musician, Buddy Berlin, swoops into her second marriage in 1961 with a bottle of brandy and four tickets to Acapulco. There he will teach her sons Mark and Jeff to swim and to speak Spanish, take Lucia to parties with movie stars. One night she awakes in the hotel room, where through the wooden shutters comes the sound of surf and scent of ginger, and finds him in the bathroom, shooting heroin. “I wasn’t as shocked as I would have been if I had known what heroin was, what addiction was.” (“That zest in him... the way he went for it, all of it,” she writes later on. “I can understand his doing drugs. I hate them for taking him from us.”) They move to New Mexico, believing their love would protect them from heroin. It does not, and yet:

They moved later to Yelapa, a Mexican fishing village you reached by horse or canoe. Their house had sand for floor, a thatched palm roof and no walls, surrounded by datura, whose profusion of white flowers “hung heavy clumsily til night, when the moonlight or starlight gave the petals an opalescent shimmer of silver and the plant’s intoxicating scent wafted everywhere in the house, out to the lagoon.” Elsewhere, hibiscus, canna lilies, four o’clocks, impatiens, zinnias, gardens of green beans and tomatoes, lettuce and squash. The boys, three of them now, speared fish and gathered clams. “Our morning began with the hundreds of roosters from town, the squawks of Teodora’s chickens,” Berlin wrote. “The gulls came with an enormous clapping and calling, a staccato swift flapping up the river, then a swoop back down, dispersing out to see, calling calling, ‘Wake up, all is well.’ Every morning, when the gulls came, for the next year or so, we would look into each other’s eyes, confirming the happiness and gratitude we felt, too fearful to actually say it out loud. And then we stopped that look, and for all I know, the gulls stopped coming.”

“The stories she could have told,” wrote Mark in his mother’s eulogy. “Like the time she went skinny dipping in Oaxaca on mushrooms with a painter friend. They freaked out when they emerged from the water, green head-to-toe from copper in the stream.” He recounts a favorite memory: “A sunset in Yelapa glinting off Buddy Berlin’s saxophone, swirls of bebop and wood smoke as Ma cooked dinner on a comal, her face radiant in the coral light, flamingos fishing akimbo in the lagoon outside, the sound of surf and pinging frogs, our feet crunching on the coarse sand floor. Doing our homework by lamplight and scratchy Billie Holiday.” He would die a year after she did, having shared her struggle with alcoholism. “There were tough times; dangerous even,” he wrote. “Ma would wonder aloud why no one came and took us kids away when it was really bad for her. I dunno, we came out okay.”

Did I mention she was gorgeous? In photos, her eyes dazzle with the frosted blue of sea glass. She’s usually tanned, wearing breathable fabrics and an impression of rapt attention, even in those from later in life. By that point she was sober and had been diagnosed with lung cancer, resulting in her attachment to a mobile oxygen tank. “You better get over your looks before you lose them,” she’d told her friend Dave Cullen. “Once they’re gone, it will be too late. You’ll never get over it.” Each photo that I’ve seen of hers contains a lilac aura (search them and see for yourself).

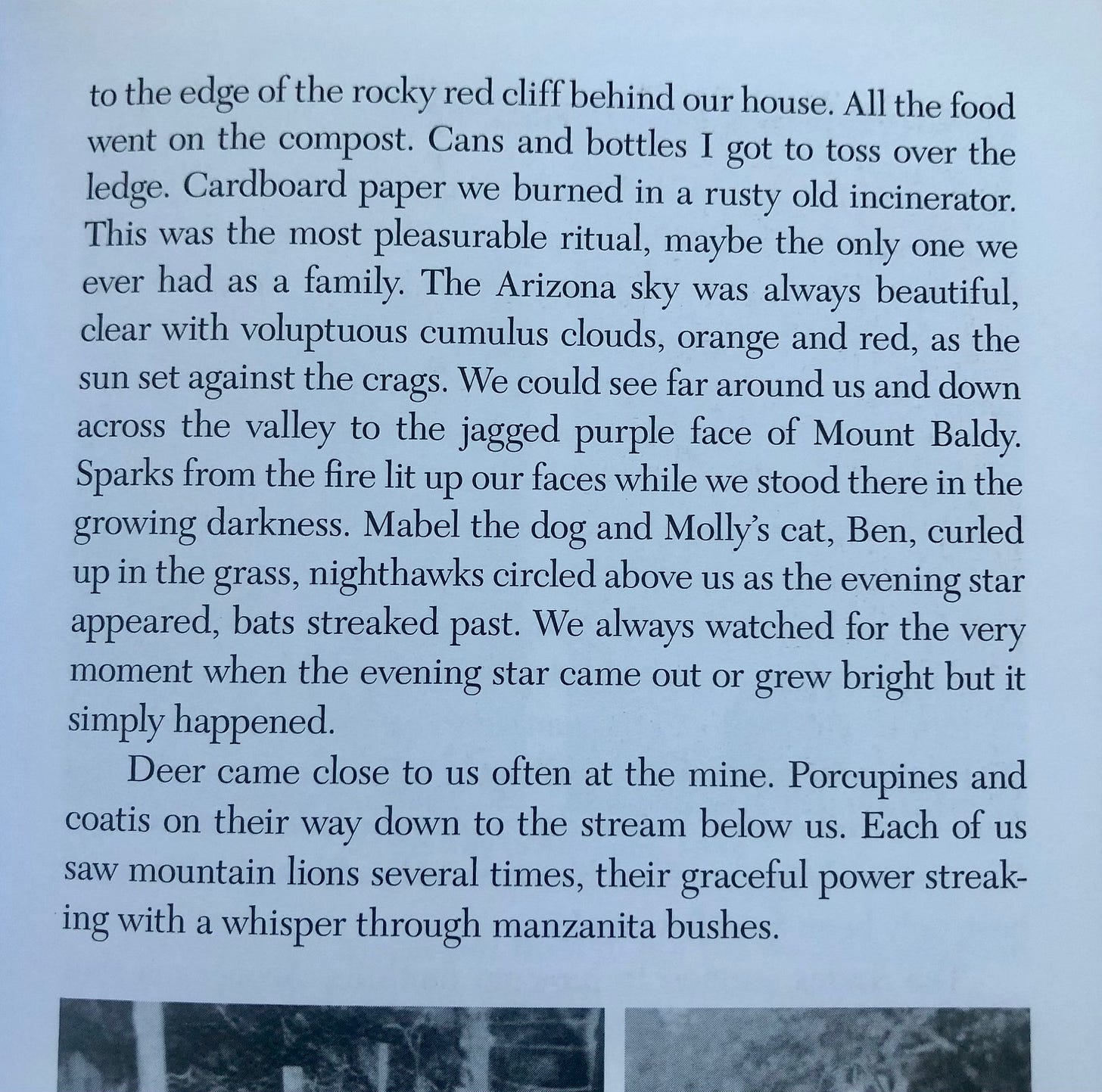

I adore reading stories from Lucia’s childhood, no longer masquerading as fiction, arriving in abstract sensory glimpses the way childhood memories do: pine branches against a windowpane in Coeur d’Alene, Idaho, the perfume of lilacs and hyacinths, an elegant lamp in the berth of a train from Spokane to El Paso at night. (“I turned on the light with the curtain open, then waved and smiled in case there was anybody out there in the woods.”) The first word she spoke was “light.”* In Patagonia, Arizona, nearby her father’s mine, the routine of taking out the trash approaches the sublime:

“Ma wrote true stories, not necessarily autobiographical, but close enough for horseshoes,” wrote Mark, her eldest son. “Our family stories and memories have been slowly reshaped, embellished and edited to the extent that I'm not sure what really happened all the time. Lucia said this didn’t matter: the story is the thing.”

* My first word? “Mailman.”