I couldn’t tell you where I was or what I did in the years 2008, 2014, or 2020, but as for my childhood aesthetic awakening, I can see it clear as day. On the wall of a dim classroom (park district summer camp 1992), a laminated poster of Henri Rousseau’s “The Dream”: a lush, dark jungle alive with fruit and flowers, lions’ dilated pupils, a long-haired naked goddess bathed in silver moonlight. That year marked the release of the first book in the series I Spy: A Book of Picture Riddles, whose elaborate still-life photo puzzles sparked a compulsion for, shall we say, “visual hoarding” that carries on today in the vortex of my “FOUND IMAGES” folder. It was around this time I became obsessed with mood lighting: lying beneath the Christmas tree, squinting through the branches til the red, blue, and purple bulbs blurred and kaleidoscoped. I would ask my parents for more Christmas lights as presents, not quite “getting” the situation, which partially explains why my apartment is presently aglow with string lights somewhere on the spectrum between “yuletide” and “brothel,” 24/7/365.

I can’t say I remember the House on the Rock, exactly; more like it imprinted upon my subconscious in the slippery way of a really weird dream. Inside it was dark and warm and vaguely Japanese, with shag carpet and low ceilings and moody Tiffany lanterns. Further within its depths was the kind of visual chaos that pleased my maximalist sensibilities: mechanical orchestras that filled entire rooms, a dizzy merry-go-round inhabited by creatures straight out of “Jabberwocky,” cases upon cases of swords and guns and butterflies and hundreds of creepy dolls lit from below as if the fires of hell blazed just beneath them. From one room lurched a 200-foot whale with fangs taller than me. In another, stylish dummy acrobats comprised a three-ring circus, elephant and all. Am I making any sense? It’s too hard to describe. But almost everyone I know who visited the House on the Rock as a kid left… changed.

They call this part of Southwestern Wisconsin the Driftless area. Technically this means the region went unglaciated in the last Ice Age, but doesn’t the phrase suggest a wild and windswept mystery? And it is indeed a wondrous place, with rolling hills and valleys as far as the eye can see, steep limestone cliffs, tallgrass prairies, deep woods of oak and ash, networks of caves, coldwater springs alive with trout, and tiny towns nestled along the Mississippi River valley. “This area of a few counties is remarkable not only for its scenic beauty but also for a kind of deeply American, even uniquely Midwestern, eccentricity, much of which is on display for travelers,” wrote Jane Smiley in a story for the New York Times in 1993 (“Wisconsin: Three Visions Attained”). She notes two local visionaries whose works are juxtaposed a few miles from one another here in the Wyoming Valley — Frank Lloyd Wright’s Taliesin, and Alex Jordan Jr.’s House on the Rock.

I like how Smiley writes about Taliesin, the 800-acre estate that Wright built into the hills of the Wisconsin River valley, at one with its surroundings as befits the Prairie Style. “The world Wright created for himself suggests a quest for purity and simplicity that seems almost evangelical — an offshoot of the recurrent born-again strain in American culture, but one that expresses itself horizontally and close to the ground rather than vertically, striving to transcend nature and the world,” she says. “The tour of the school and house are made to seem much like a religious experience. Certain rooms are off-limits; Wright and his battles and trials are discussed as if they have just happened; early associates who are still living at the house come out and tell stories (did I almost say parables?); a communion-like tea is served; shoes are removed before entering... Enthusiasm is the order of the day, but a pure, aesthetic, expansive enthusiasm, nothing low or acquisitive.”

“For that,” she writes, “there is the House on the Rock, five miles back down the road.”

According to a story that’s almost certainly untrue, Alex Jordan Jr. built his House on the Rock to spite Frank Lloyd Wright, who’d insulted his father many years before. In truth, the college dropout simply fell in love with the 70-foot rock tower jutting above the Wyoming Valley near the village of Spring Green. Jordan bought Deer Shelter Rock and the wooded land around it, and in 1945 began building a weekend retreat upon its summit, supposedly without a blueprint and with stones he had hauled up the cliff on his back. (His father supplied the funds.) The original 13-room house is done up like the Graceland of the Midwest: cramped and dim and pleasantly musty, with floor-to-ceiling shag carpet, giant stone fireplaces that threaten to burn the place to ash, and canted banks of windowpanes that merely hint at the idea that you are balanced on a rock teetering above the forest. With six-foot ceilings and velvet seats barely knee-high, you start to get the sense that the place was made to crawl through, drunk on martinis and preferably nude.

Jordan began charging visitors to view his kooky getaway, a marvel of engineering and a puzzle of design. The money that poured in, he reinvested in the house’s ongoing expansion, which spiraled on until his death in 1989. (That November, a small plane rained his ashes over Deer Shelter Rock.) And it is mainly these expansions which draw over a million tourists to House on the Rock each year — room after freaky room of such a magnitude of strangeness I’ve yet to witness anywhere else, through which you wind your way on a path that seems to descend into an unknown circle of Hell, with stops along the way for ice cream cones and greasy pizza. Jordan first envisioned the Organ Room — a cavernous, blood-red pit where catwalks snake you past the world’s largest pipe organ, beneath its largest chandelier, and through a confounding maze of industrial detritus and gnarled birch trees — as his riff on Dante’s Inferno, inspired by the etchings of Giovanni Battista Piranesi whose impossible spaces represented prisons of the soul.

Jordan considered the Organ Room to be his masterpiece, but it’s the Carousel Room I think of when I think House on the Rock. The largest carousel in the world, it’s comprised of 269 non-horse creatures repurposed from early 1900s carnival antiques, lit by 20,000 bulbs and 189 chandeliers and blaring loud circus music as it spins through the darkness at troubling speed. (In Neil Gaiman’s American Gods, so I’m told, he uses the Carousel Room as a metaphysical portal where Old Gods meet. “I had to tone down my description,” he said, “in order to make it believable.”) Then you look up. From the ceiling dangle an army of mannequins with Valium eyes, hundreds of them sprouting angel wings from their gossamer dresses which part to bare plastic nipples. The Day of Reckoning has come upon the Uncanny Valley. The merry-go-round spins, the music clangs on, and I think of Laura in Fire Walk With Me. “Do you think that if you were falling in space, that you would slow down after a while or go faster and faster?” Donna wonders. “Faster and faster,” says Laura. “And for a long time you wouldn't feel anything. And then you’d burst into fire. Forever. And the angels wouldn't help you. Because they’ve all gone away.”

An hour’s drive north from the House on the Rock is a place I’ve written about before on this here newsletter, a totally wretched place that means more to me than words can say. I learned to swim here, to love the smell of lake water and pine trees, to worship the authority of my idol, Smokey Bear. My happiest childhood memories are set in the woods along Lake Delton — man-made centerpiece of Wisconsin Dells, waterpark capital of America. Here I fed ducks big hunks of white bread, hooked trout who stared into my soul with one reproachful eye, played games of rummy and euchre that went on well past bedtime, then fell asleep to the clack of the fan and the sound of my grandmother’s snores. Later I’d learn that the Dells was for babies, a scenic tourist trap for F.I.B.’s (Fuckin’ Illinois Bastards) and people with type 2 diabetes. I’d hardly scratched the surface of Wisconsin’s mysteries.

As to the cabin where my family stayed each summer, I can picture it as if the year was 1992: sticky pine needles carpeting the woods around Lake Delton, hot dogs hissing on the grill, porch swing groaning under the weight of three sisters at once. The face of Smokey Bear gazed magisterially over the parking lot from a tin sign on the stairway — the real Smokey, kind but serious, before the lamestream media turned him into an emoji. The message he imparted hit me like a ton of bricks: standing in the way of the place burning to ashes, and with it everything I loved, was me, and me alone. He approached me as an equal, though I was maybe 5, asking me simply to care. I feared his disappointment second only to my mother’s, having seen his grave expression on a much scarier poster where he stood, shirtless in jeans, before an evil wall of flames: “This shameful waste WEAKENS AMERICA!” Meanwhile his bear friends knelt and prayed, presumably to the effect that our great country might survive the spectacle of human folly.

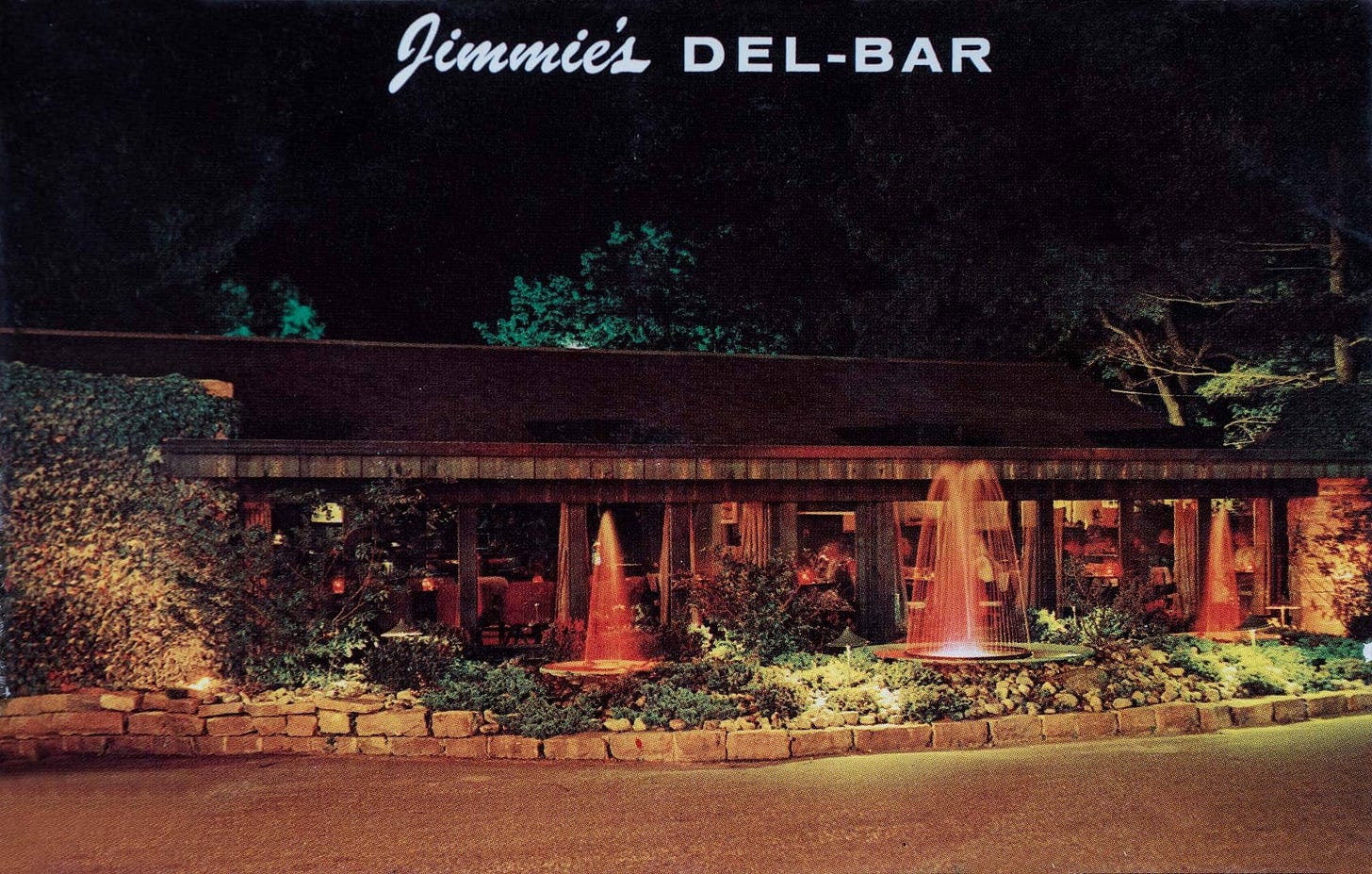

When my parents were feeling fancy we’d have dinner at the Del-Bar, a moody supper club with Rat Pack vibes and Prairie-style design, and a fixture of Wisconsin Dells since 1943. Even then I was aware that the Dells was pretty tacky, with its filmy Lazy Rivers down which obese families floated, its “trading posts” hawking rude shot glasses and garish tie-dye t-shirts. (Returning to school one fall, especially tan and sporting Minnetonka moccasins I’d picked up at one such tourist trap, I spread the lie that I was an “Indian” throughout my third grade class.) But not the Del-Bar, where shrimp was served in mirrored silver bowls, French onion soups bubbled with cheese, and char-broiled steaks came topped with crab. My fit and bookish mother, the queen of self-control, allowed herself a glass of wine and granted me a kiddie cocktail swimming with neon cherries. My heart burned for adulthood, having reached an understanding that the youth my schoolmates cherished was just something to pass through.

Years later, after a week of heavy rain, floods would bust the levee which held Lake Delton intact, draining 700 million gallons of water into the Wisconsin River in two hours’ time and leaving in its place a mud pit three stories deep. You could stand over the edge, as my sisters and I did later, watching the fearsome currents rush through the hole where our childhood used to be. The flood was June 9, 2008. My mother had died the morning before (breast cancer, stage 4). By then, years had passed since I’d been in those woods; she’d been too sick, and I too cool to partake in nostalgia at the age of 21. As allegories go, it was all quite heavy-handed. Treasure hunters descended in subsequent weeks to sweep the muck with metal detectors, emerging from the pit with motors, guns and bones. In a dusty corner of a Baraboo antique store a decade or so later, I came upon an art object: a dozen tarnished wristwatches a local man had found inside the void, which he’d affixed to plywood and captioned shakily in Sharpie: “ON JUNE 9th 2008 TIME STOPPED ON THE BOTTOM OF LAKE DELTON.”

I pulled into the Del-Bar before the end of happy hour, where a crowd of chatty regulars had crowded around the bar. “Was it your silo that blew up?” a gray-haired fellow to my right inquired of the waitress, who slowly shook her head. “No, I don’t recall our silo blowing up. Maybe that was Sleepy’s farm?” I ordered an old-fashioned (brandy, sweet), wedge salad and some meatballs, chatting with the 85-year old fellow, a rather raunchy man named George who paid my tab, though nothing’s free. “I raised hell all my life,” said George, downing his Tom Collins and waving for another. “I once stole a church bell. You know how hard it is to steal a church bell?” I said goodbye and headed toward Lake Delton, where the sun was just beginning to fall.