“You want your dreams to come true?”

“My dreams? What dreams is that?”

“What’s your American dream?”

“I don’t have any dreams anymore.”

“You don’t? You can’t stop now. What’re you gonna do, sit around outside of a trailer? We’ll film you sittin’ outside of a trailer, man, but we ain’t gonna live sittin’ outside of a trailer.”

“Where else am I gonna sit?”

“Look man, all people are yammering and yammering about is the American dream…”

“It’s half past three already.”

“All they’re talkin’ about is the land of opportunity. All it is is lip service.”

“Time for me to eat.”

“Here, we’re livin’ it. And I will be goddamned if I don’t get the American dream.”

— MARK & BILL, AMERICAN MOVIE

“I was a failure,” says Mark Borchardt, and that’s the first thing you hear in American Movie. “I was a failure and I’d get very sad and depressed about it, and I can’t be that no more.” He’s pushing 30, the year is somewhere in the ‘90s, and he is driving in the dusk through Menominee Falls, WI, a blue winter world warmed by yellow streetlight glow. “I really feel like I betrayed myself bigtime,” he goes on in his thick Midwestern accent. “When I was growin’ up, I had all the potential in the world. Now I’m back to being Mark who has a beer in his hand and is thinking about the great American script, the great American movie. And this time I can’t fail, I won’t fail, it’s not in me. Not just finishing films, or in the long run getting some money, but right now I feel like it’s 5, 10, 15 years ago and I’ve got the same options again. But this time it’s most important not to fail — not just to drink and dream, but rather to create and complete.”

I grew up thinking of the Midwest as a void of style and intrigue, though I could not have been more wrong. “More poetry is said to come from Wisconsin than from any other state in the Union,” reads a clipping from an 1885 issue of the Badger State Banner, erstwhile local paper of a former mining town, Black River Falls, WI. The quote is presented in Michael Lesy’s 1973 book Wisconsin Death Trip, a work of what I’d call interpretative photojournalism. Studying at the University of Wisconsin in the late ‘60s, Lesy happened upon a trove of portraits from the late 1800s that were deeply, hauntingly strange. Some showed faces: unsmiling, wild-eyed, Scandinavian, touched by some obvious madness. Others showed tiny, horrible coffins inside of which were infants, eyes shut in what looked like sleep. Camps of murderous-looking loggers glared among the snowy pines; a laughing woman wrapped live snakes around her neck. The photos were taken between 1890 and 1900 by Charles Van Schaick, town photographer of Black River Falls. Arranged by Lesy, they convey a collective psychic crisis of the sort I witness regularly on public buses and trains.

Lesy scoured the archives of local newspapers from the time the photos were taken, and what he found was chaos: unsentimental accounts of suicide, arson, infant death, murder, psychosis. Homes are tormented by demons and ghosts. Men set fires for pleasure, or freeze to death in their sleep. Women throw themselves in front of trains and into wells, or slash their own throats with sheep shears. Entire families are killed by disease: diphtheria, cholera, smallpox. Reports of these happenings, presented without comment, appear alongside Van Schaick’s photographs, and the cumulative effect is powerfully bleak — the American dream, gone terribly wrong. But just past the darkness is an idea: that even the most modest lives, like those of the people of Black River Falls, are suffused with psychedelic mystery, like when an old man cheats his undertaker by leaping from the coffin in which he had been placed.

But I digress. In American Movie, which won the Grand Jury Prize for Documentary at Sundance ‘99, we spend two years with Mark Borchardt — independent filmmaker, Army vet, paperboy, janitor at a cemetery, drunk, father of three. We see him opening mail in his messy computer room: “This is gonna be interesting: the IRS, Wisconsin, amount delinquent $81.71, oh man, resulting in a lien on any personal property that you own within 10 days of this notice. September 6th, and we’re October 19th. Luckily it’s just $81, what are they gonna take, y’know, my Night of the Living Dead book? ‘Legal actions,’ unbelievable… Your AT&T Universal Card has arrived? Oh god, kick-fucking-ass, I got a MasterCard! I don't believe it, man. Life is kinda cool sometimes.” The camera scans his bookshelf: Notes by Eleanor Coppola, Spike Lee’s By Any Means Necessary, Hunter S. Thompson’s Songs of the Doomed: More Notes on the Death of the American Dream.

Mark is lanky and rakishly handsome, with a greasy mullet, big glasses, and Salvation Army clothes. For half his life, he has made movies starring himself and his friends: strange black-and-white thrillers like The More the Scarier, a silent film he shot at age 14. “Yeah, I was in The More the Scarier III,” says his buddy Mike Schank, whose Buddha-like demeanor he earned from drug abuse. “We were ridin’ into a cemetery in the back of a truck, and we were drinkin’ vot-ka and I was playin’ my guitar.” At present, Mark is juggling two films: a “35-minute direct-to-market thriller shot on 16mm black-and-white reversal” called Coven, now two years in the making, with whose profits he hopes to fund his first feature, Northwestern. “There’s no excuses, Paul,” he tells the only other person in the production meeting. “No one has ever paid admission to see an excuse. No one has ever faced a black screen that says, ‘Well, if we had this set of circumstances we would’ve shot this scene, so please forgive us and use your imagination.’ I’ve been to the movies hundreds of times. That’s never occurred.”

I imagine many people in the years since its release (around this time in November of 1999) have interpreted American Movie as a comedy, or felt sorry for Mark and his low-down band of brothers, who drink vodka to excess, compulsively buy scratch-offs, and seemingly have nothing better to do than help their friend shoot movies that he may never complete. (“This is his whole life, making this one film,” says Dean, in charge of Props & Special Effects. “It’s like, yeah, I can lose ten weekends to help you do that.”) But Mark, for all his failures, is obviously a genius: a wildly charismatic speaker and a genuine auteur, with a vision undeterred by the strictures of real life. In a cheerless rented boardroom, he describes Northwestern’s intro to the film’s haphazard crew: “Beautiful stunning black-and-white shot, right now at the magic hour, as we float past dilapidated duplexes, worn trailer courts — and I’ve been location scoutin’ em, so when I do this [makes his hands a frame] I’ve already got what’s in between my hands. And right then at that moment, people are gonna say, ‘My god, I’m glad I’m sittin’ here, because I’m actually seein’ something for once!’ We get to see AMERICANS and AMERICAN DREAMS, and you won’t walk away depressed after seeing this, period!”

Ask Mark about his inspirations and you might think he’d rattle off, “Dawn of the Dead, Texas Chainsaw Massacre, Night of the Living Dead,” but what you get is something else. Responding to the prompt “Talk about your earliest influences” in an interview from 2004, he replies: “When I was about 5 years old, I didn’t get into television or anything like that. I remember distinctly at night sitting on the street curb, looking up at the stars, and thinking, ‘Isn’t life a trip? Isn’t this cool?’ And that’s basically when I started losing touch with other people.” In a scene in American Movie from 7 years before, a writer from the Menominee Falls Tribune asks the same question ahead of Coven’s premiere. “When I was growing up and drinking, the people that I was around, they were the Americans who were still fightin’ the West with a bottle of vodka in their hand, man,” Mark answers instantly. “There was still territory out there, in the mind, or around the block, or something like that.” “Expand on that a little,” the newspaper man says. “Okay, listen, there was no such thing about college or religion or anything; there was drinking. Drinking, drinking, drinking,” Mark says. “And everything would revolve around that: the money, the time spent, everything. It was America at that point.”

Somehow it took three or four viewings of American Movie for me to realize how much of Mark’s work was about alcoholism. His brothers raise their eyebrows at his movies’ gory themes, which he is adamant are based in his own life. Then again, for all its slapstick slasher trappings, the plot of Coven regards an alcoholic writer ensorcelled by a woman to attend an AA meeting, which is where the trouble starts. Addiction saturates the life of Mark and most of his friends, like Mike Schank, who nearly died guzzling liquid PCP, whose AA sponsor now drives him to his Gamblers Anonymous meetings. (“Here’s what I think of the lottery: I think it’s like, when you play the lottery, sometimes you win and sometimes you lose,” he says serenely, beaming a Buddha’s smile. “But it’s better than using drugs or alcohol, because when you use drugs or alcohol, especially drugs, you always lose.”) It is the second-biggest hindrance to Mark’s work, other than money. “Coven, man, we gotta get this sucker done though, seriously,” he tells the camera, loitering by a lumber scrap yard beneath an empty winter sky. “Last night I was so drunk, I was calling Morocco, man, trying to get to the Hotel Hilton at Tangiers in Casablanca, man. I mean, that’s pathetic, man! Is that what you wanna do with your life? Suck down peppermint schnapps and try to call Morocco at two in the morning? That's senseless!”

By the time of the 2004 interview linked above, Mark had quit drinking cold turkey, but his feature film Northwestern wasn’t close to being done. “It’s far too complex to get into,” he said, “because when I make a film, it’s not, ‘Oh what a neat idea,’ but rather, ‘What have I experienced in life? What is my reaction to it? Where would I like to see my life go? How could I transcend this emotional and narrative information?’ And as you go through life, your ideas change, your experiences change, and then if you’re starting to make a film, the film needs to be modified to this new way of thinking.” As for booze: “I wish that was my big obstacle in life, but it certainly isn’t,” he admitted. “The great people who have peace of mind and personal success are one with themselves. People always come up to me like, ‘Hey, what’s your next movie? What’s going on?’ And to me, it means absolutely nothing, because I have to become one with myself. And I’ve never been that. I am trying to achieve that in life. That is the most important thing, and nothing will come out of me until that is continually worked out.”

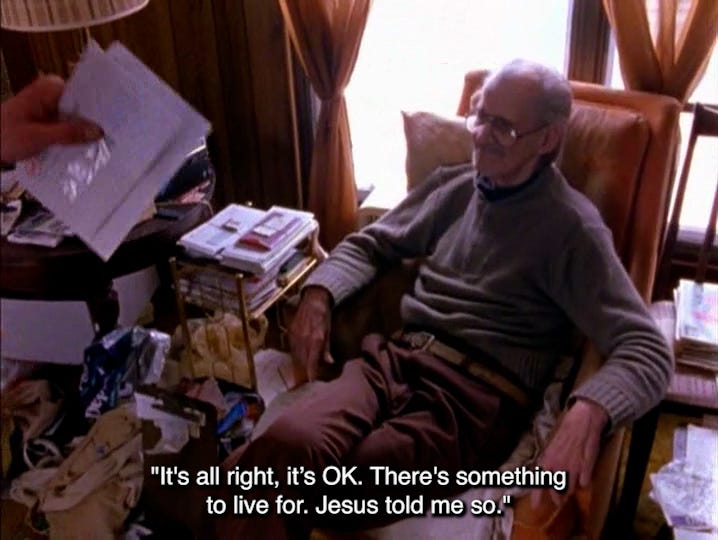

I hesitate, and maybe Mark would too, to describe alcoholism’s influence as purely negative, the same way I see everything as a collector of stories: the more you lose, the more you win. In my own life, the experience of being a drunk amongst drunks has influenced my writing more than just about anything else. What makes American Movie endlessly captivating are the striking profundities of regular neighborhood guys — the “religious joy,” as Mark puts it, of simply being around them, hearing the great things they have to say. That comes through most of all in scenes with Uncle Bill, who I mistook for Mark’s grandpa, frail and loopy as he is. But Bill is a poet, too, who on occasion warbles strange songs for his dead wife: “So goodbye, dear... hope you’re in heaven where you belong... I was wondering, do they smoke cigarettes in heaven? I don’t think so. I don’t think so... I still love you. I’ll visit your grave every day... not every day, but... I’ll visit it sometime, if I ever find it...” The shimmer in Mark’s eyes as he watches this performance inside his uncle’s trailer is a mix of true love, heartbreak, and the ecstasy of witnessing a unique moment in time, one that’s never been and will never be again. “Are these songs you wrote?” asks the cameraman, to which Bill replies simply, “This is what happened to me.”

25 years later, Northwestern hasn’t come out, though I doubt Mark’s too concerned. These days he makes music videos at a rapid clip and is currently at work on The More the Scarier VI; this I know from his polite rejection of my interview request regarding American Movie’s 25th anniversary. (“None of the aforementioned has anything to do with me,” he said matter-of-factly, wishing me well. “But when TMTS VI gets finished, that could possibly be discussed.”) He’d been approached by Hollywood many times in the 2000s, but even then, working a factory job designing window shutters, that wasn’t his cup of tea. “Yeah, I have offers of money, blah blah blah. But I’m an adult who sees the other end, sees where I’ll lose control,” he told an interviewer in 2004. “They’d make the movie in color, change things, because they have to make money. I’m making an aesthetic investment from the heart. The worlds do not integrate.” I like following his Twitter, where he posts messages like this: “Another atmospheric November day. Another chance to move forward in the creative realm. Make the most of it.”

American Movie is showing at the Gene Siskel Film Center on Dec. 6 and Dec. 14.