“Sometimes it’s difficult to put in words or even think what it is that we are all looking for.”

— DAVID LYNCH

This was the winter I became obsessed with dreams — the winter I found dream logic in every place I looked. A record I’d reviewed by Johnny Coley (“transcendental poetry meets Southern nightmare jazz”) had reminded me of that one scene from Twin Peaks: The Return, where Monica Bellucci quotes from ancient Hindu scriptures. “We are like the dreamer who dreams, and then lives inside the dream,” she tells the FBI director played by David Lynch. “But who is the dreamer?” You might follow this logic and wind up at the idea of the American Dream as a mass hallucination, a tragic or funny notion depending on the day. In any case, around this time, I pulled a book out of the shelf — Memories, Dreams, Reflections, the 1961 autobiography of Carl Jung.

“My life is a story of the self-realization of the unconscious,” writes Jung, age 81, to open the prologue. He rejects the language of science to articulate the subject; our inner lives, he says, are best expressed by way of myth. Over many years, he learns that myth connects us to life’s meaning, linking us to our ancestors and to a world outside of time to which belongs the earth, the sun, the moon, the night, our dreams. He sensed that city life belonged to a different order of reality than that of his country childhood — “among rivers and woods, among men and animals in a small village bathed in sunlight, with the winds and the clouds moving over it, and encompassed by dark night in which uncertain things happened.” This was not any old location on a map, but a superhuman world suffused by God with secret meaning.

“But apparently men did not know this, and even the animals had somehow lost the senses to perceive it,” Jung went on. “That was evident, for example, in the sorrowful, lost look of the cows, and in the resigned eyes of horses, in the devotion of dogs, who clung so desperately to human beings… People were like the animals, and seemed as unconscious as they. They looked down upon the ground or up into the trees in order to see what could be put to use, and for what purpose; like animals they herded, paired, and fought, but did not see that they dwelt in a unified cosmos, in God’s world, in an eternity where everything is already born and everything has already died.”

I can see now that the myth which gives my adult life meaning — which clarifies the question posed by my very existence, and links me to a collective spirit outside space and time — is, well, Twin Peaks. Alternatively, I could say that before I became Jung-pilled, it was Twin Peaks which re-established the role of myth in navigating the great mysteries of life. (“Mysteries precede humankind, envelop us and draw us forward into exploration and wonder,” wrote Mark Frost in The Secret History of Twin Peaks, differentiating them from secrets; those are the work of man.) Though Lynch himself wasn’t a fan of psychoanalysis, Frost has long cited Jung as a major influence. I sense a Jungian aura about Deputy Hawk and Major Briggs, whose rigorous self-study has opened them to all forms of cosmic possibility. “This is where we’re headed, but there’s no road. The road is gone,” notes Sheriff Truman in The Return Part 11, typing secret coordinates into Google Maps. But Hawk unfurls a yellowed map, covered in hand-drawn symbols. “We’ll understand a lot more when I explain my map,” he says. “This map is very old, but it is always current.”

Jung began writing his memoir in 1957 — 12 years after the first nuclear detonation, and one year after the scene in The Return Part 8, where from the Trinity Test site hatches a cursed egg. The final pages of Memories, Reflections, Dreams address the reality of 20th century evil. “We must learn how to handle it, since it is here to stay,” he writes, though “how we can live with it without terrible consequences cannot for the present be conceived.” Myth once helped us to fathom the incomprehensible, but in an era governed by rationalism and reason, “our myth has become mute, and gives no answers.” And so we meet the question of evil empty-handed and confused, certain we are witnessing a turning point in time, though we imagine that it has to do with politics and science, and not, as Jung describes it, “the long-since-forgotten soul of man.” He gestures through the ages to the notion that the devil had created the world, and wonders, “What would these old storytellers have to say about Hiroshima?”

In Twin Peaks, as in every David Lynch film, the problem is simple: we originate in the unified cosmos, and nothing can take away from the concept of divine wholeness. But somewhere, and for some reason, occurred a splitting of that wholeness, and there emerged a realm of light and one of darkness. The dichotomy penetrates into the human psyche; to return to wholeness, we must integrate the halves. “Therefore the individual who wishes to have an answer to the problem of evil, as it is posed today, has need, first and foremost, of self-knowledge, that is, the utmost possible knowledge of his own wholeness,” so says Jung. “He must know relentlessly how much good he can do, and what crimes he is capable of, and must beware of regarding the one as real and the other as illusion. Both are elements within his nature, and both are bound to come to light in him, should he wish — as he ought — to live without self-deception or self-delusion.”

But the soul will always have a home in unity and light, though it may forget its origins or believe itself too corrupted to return to the eternity of divine consciousness. “That is the ultimate illusion, and the bleakest,” writes B. Kite in a great essay on Lynch from 2019. “The soul’s essence remains untouched and untouchable, and after however many cycles of rebirth its eventual homecoming is assured, has happened, is perpetually happening. It only remains for the soul to wake up in order to realize it never left.”

I began this newsletter in December 2020, with a name I’d found graffiti’d on a local Dunkin’ Donuts and no strong feelings on exactly what I’d write. At the time, I’d all but given up on writing for money, working instead as a bartender, then hosting and waiting tables at a hamburger restaurant. (Meanwhile I was dating my most Lynchian boyfriend, whose eyes I once witnessed turn completely black.) Mortified to see what I was on about back then, I hesitated to review the first SCSG post. But apparently I’m something of a broken record — what preoccupied me then is what preoccupies me now. I wrote about The Twilight Zone (“the only thing that makes sense to me these days, like I’m not nuts for thinking I’m living someone else’s bad dream”) and how it reaffirmed my distaste for rationalism. Then I talked about a movie I had just become obsessed with: 1962’s Carnival of Souls, which begins with a car crash, and though we follow its survivor through the Utah of the mind, eventually we find she has been dead all along. I ended the post with a quotation from Rod Serling:

“You see — no shock. No engulfment. No tearing asunder. What you feared would come like an explosion is like a whisper. What you thought was the end is the beginning.”

As for the second-ever SCARY COOL SAD GOODBYE post — take a wild guess what that one was about.

SCARY COOL SAD GOODBYE 02

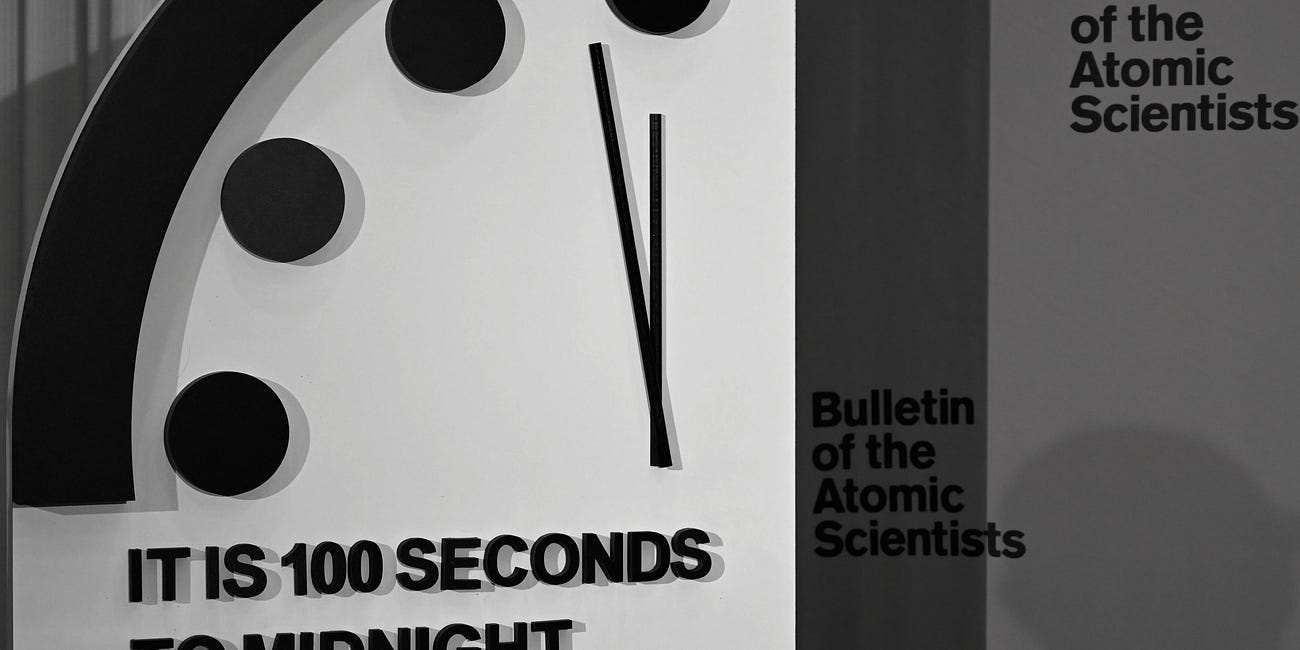

As the year winds its wretched little way to Midnight, I thought I’d take some time to reflect upon my favorite records of 2020, testaments to resilience in the face of great uncertainty. Psych; fuck that shit! I can name maybe seven new albums I remember enjoying more than once this year, and one of them was

In Lynch’s myth, the trouble is not what is to happen, but what has already happened; the epiphany is that it is happening again. The day of reckoning is behind us; America collapsed long ago; Laura Palmer was dead before Twin Peaks even started. It would appear that we have sleepwalked into chaos, waking to find the world unrecognizable. Uprooted from our past and robbed of our guiding instincts, we have been swept into the darkness of the future, waiting for the promised sunrise; we fail to recognize, as Jung says, that “everything better is purchased at the price of something worse.” But then, from somewhere in the cosmos, Laura corrects me — “I AM DEAD, AND YET I LIVE.”

“This is ‘now,’ and now will never be again,” says the Log Lady in the pages of Mark Frost’s The Secret History of Twin Peaks. “We come from the elemental, and return to it. There is change, but nothing is lost. There is much we cannot see — air, for instance, most of the time — but knowing our next breath will follow our last without fail is an act of faith. Is it not? Dark times will always come, as night follows day,” she goes on. “A dark age will test us all, each and every one. Trust and do not tremble in the face of the unknown. It shall not remain unknown to you for long.”

I’d like to pair that thought with one from the last few pages of Memories, Reflections, Dreams. “The world into which we are born is brutal and cruel, and at the same time of divine beauty,” writes Jung. “Which element we think outweighs the other, whether meaninglessness or meaning, is a matter of temperament. If meaninglessness were absolutely preponderant, the meaningfulness of life would vanish to an increasing degree with each step in our development. But that is — or seems to me — not the case,” he says. “Probably, as in all metaphysical questions, both are true: Life is — or has — meaning and meaninglessness. I cherish the anxious hope that meaning will preponderate and win the battle.”