Then I’m throwing dice in the alley,

And Officer Leroy comes up, and he’s like, “Hey, I thought I told you —”

And I’m like, “Yeah, whatever!”

Then up comes Zaphron, and I’m like, “Yo Zaphron, what up?”

And he’s like, “Nothin,” and I’m like, “That’s cool.”

Cause this is my United States of whatever…

Life had become strange overnight. I blamed the lunar eclipse. My cat had stopped eating; her cancer had spread. I cried off my fake eyelashes as we cuddled in bed, her breath coming shallow and fast. With the window open, she could hear the sounds of spring, the purr of mourning doves nesting on the AC unit, and as she sat there in a sunbeam with her eyes closed, I knew she understood the situation. When all was said and done, my beloved beach apartment seemed hideously empty, no longer home at all. The two of us had lived there since my ex had left her with me and shipped off to Korea in 2017 — to “find himself,” he’d said, though of course I knew the truth. I’d sent several unhinged emails to his poor Korean girlfriend, demanding money or I’d give the cat away. Then our love grew for each other (mine and the cat’s, not the Korean’s), a purer love than I had ever found in men. If anything, the 20 years I’d spent consumed by romantic turmoil now seemed quaint. It was obvious by now there were worse heartbreaks to be had.

I’d been reading Lisa Carver, trying to feel alive. “Awareness of anything is all there is. All the world, all of life, is only the story we’re telling ourselves in that moment,” she’d told me via email in 2022. Looking back, I see that what I thought was my own motto, I’d in fact stolen from her. (“How’s life?” I’d asked as she sat in a French hospital with several organs missing, to which she cheerfully replied: “How could it be anything other than good, as a writer? The more you lose the more you win.”) Recently I’d picked up her new book, Lover of Leaving, whose table of contents include “a diary of losing all my blood and coming to in a French hospital where the nurses smoked cigarettes and gossiped loudly all night long,” “an article about when I went crazy and found out from a feather that I was God,” and “going to Peru where a shaman put her hand through the back of my skull and pulled out all this stuff and I have never felt so clean.”

From Lisa’s French hospital diary, post-cancer diagnosis:

“The Ouija board said I’d live til 84 and I always believed it and still do. But just in case, I would like anyone reading this to know it was a very good life, I did every single thing I wanted to and nothing that I didn’t. Wonder is our natural state of being, I believe, and when you don’t feel it, something is wrong, and all you have to do is identify it and then leave it behind. It’s so easy to be happy. You can get there two ways: walking away from something not good for you, or simply walking, in the sun or rain or starlight or snow. I don’t know if that advice applies to everyone. Bruno says I’m always escaping rather than experiencing tough things, and maybe that’s true. I just don’t see any reason to ‘work through’ anything. I’m not big on trying. That includes being okay with dying.”

I returned to The Pahrump Report, my favorite book of Lisa’s, in which she sells all her belongings, cuts off all her social ties, and lives among the grizzled cowboys of Pahrump, Nevada, who instead of moving into senior living centers “came here to be left alone to smoke and drink and gamble away their children’s inheritance in bitter pleasure.” She lives with her third husband in a home with no electricity or walls, until he asks for a divorce, and then she lives there alone. “Yet… I do feel at home in the world in general, and in specific,” she writes. “I feel like everything is going to be okay and even good. I feel loved, nebulously, despite there being no sign of it anywhere around me. I look at the sky and I feel happy.” In attempt to set the mood, I brought it with me to the desert, where I’d agreed to help my father clean out his Palm Springs residence. Not by choice, he’d moved this winter into a nursing home.

My poor, well-traveled cat had visited Palm Springs’ airport before, I remembered upon landing. Tony and I had brought her with us in April 2016 when we’d come to Joshua Tree a month or so after we’d met. How we survived our week there is hard for me to say, given how far from life we were, and how we had no car. (A hazy memory appears of a taxi ride to Vons for a week’s worth of frozen hamburgers, tequila, PBR.) Then Tony’s mom arrived from Tucson and we all drove to Gonjasufi’s house to talk politics on the porch while a bunch of long-haired, shirtless kids ran circles in the dirt. Back at the airport later with our kitty in her bag, I vaguely recall a fight about… well, who knows, whatever… yelling so much they almost didn’t let us on the plane.

I had resolved to work my way out of my present slump, which by day meant packing plates and lamps and schlepping them to Goodwill, arranging furniture deliveries to the consignment store, writing my little blog posts, conducting interviews, and planning a “Southwest Special” for SCSG this spring. Then I would drive 2,000 miles through Arizona, New Mexico, Texas, Oklahoma, and whatever followed next, and somewhere along the way, I would feel happiness again.

They do graffiti differently along the two-lane highway that traced the Southern edge of Joshua Tree National Park: instead of using paint, they spell their messages with rocks. Black rocks on white rock backgrounds declare things like “J ♡ M,” or “RIP,” or “Free So-and-So,” spread out along the train tracks for what must be 20 miles. I pass what used to be a gas station, now more of a hanging rack for some 200 shoes swaying morbidly in the breeze; what claimed to be an auto shop, though all I saw were stacks of tires painted with urgent bulletins: “NO TREAD ON ME,” “SOLAR DESTROY LIFE.” Behind an abandoned liquor store, two dozen falling-apart trailers formed a sort of Mad Max neighborhood through which I glimpsed the passage of Woodsmen-like figures, or maybe I was seeing things. Beneath a YouTube video of the same liquor store (“McGoo’s”) collect stories from when the place was booming, before the solar farms infested the Mojave desert: “When I was a kid, Stanley Ragsdale would trade us a six pack of RC Cola for every rattlesnake we brought in. He would tan the hides.”

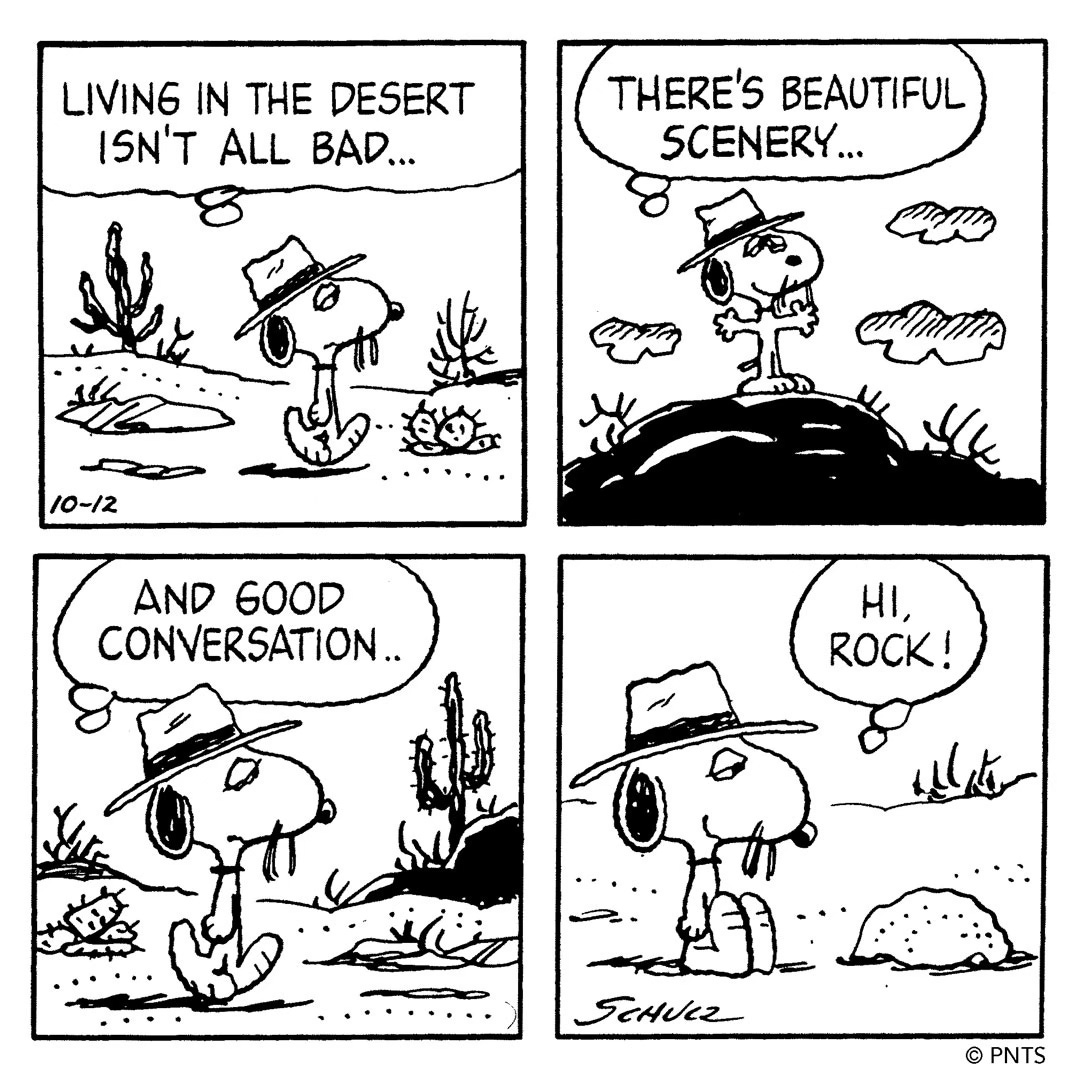

Signs began to point to “Needles” and I nearly lost my mind. Alone with my cat in the post-Tony months of winter 2018, I’d pass the hours scanning Google Maps, zooming in on desert towns with interesting names — Truth or Consequences, Chloride, Surprise, Needles. For some reason or another, Needles stuck in my craw. Named for the sharp peaks of the nearby Mohave Mountains, the town was founded in 1883 where three railroads joined together, and later became a stopping point along the Mother Road. (It is the Joads’ first California stop in The Grapes of Wrath, which naturally I carried in my backpack.) On any given day in summer, there’s a good chance that Needles is the hottest place in the United States; in August 2012, the town broke the world record for hottest rainfall ever recorded on a 115° day. It is the former home of the cartoonist Charles Schulz (hence Snoopy’s brother Spike, longtime resident of Needles) and of the poet Alice Notley, who wrote a good one in the ‘90s from the totally un-Needles-like Iowa Writers’ Workshop:

“You can write your first poems

thinking you might as well

since the most stupid people in the universe

are writing their five hundredth here.

I'm doing that now. What

difference does it make.

I like my poems. They're

as good as rocks.”

I don’t mean to lead you on, for there was no time for Needles if I were to make it to Williams, Arizona before dark. The mountain town nestled in the midst of the world’s largest ponderosa pine forest has been known since 1881 as the “Gateway to the Grand Canyon,” an hour’s drive from the national park’s South Rim. Once a rough and rowdy settlement of saloons, brothels, and opium dens inhabited by cowboys, lumberjacks, and railroad men, Williams would become the last stretch of Route 66 to be bypassed by Highway 40 in 1984, ending the great American roadway’s 59-year run. Still holding out along the downtown strip are crumbling ‘40s auto courts, Streamline Moderne diners, and a handful of trading posts hawking turquoise jewelry, Navajo rugs, and Kokopelli ephemera. I stopped for dinner of Cobb salad and coconut cream pie in a pine-paneled restaurant whose coffee bar served such delights as the Doc Holliday Steamer or the Sundance Kid Spiced Chai. Then the compass in my heart sent me to the Canyon Club.

Every surface of the Canyon Club (which first opened its doors in 1949) was posted up with dollar bills, draped in American, Arizonan, or POW MIA flags, or plastered with faded yet ever-timely stickers: “NOBODY’S UGLY AFTER 2:00 AM!” “POKE SMOT!” “RIDE FAST EAT PUSSY!” “LIBERALISM SUCKS!” What remained of the daylight filtered through glass bricks as I pulled up a stool beside a dozen of what seemed to be locals. No sooner had I taken my first sip of Coors Light than an unassuming woman took hold of a microphone and began to sing along to a song whose lyrics were far more rousing than I’d remembered:

“Yeah, darlin’, go make it happen

Take the world in a love embrace

Fire all of your guns at once and

Explode into space

Like a true nature’s child

We were born, born to be wild

We can climb so high

I never wanna diiie…”

It appeared that Sunday was karaoke night at the Canyon Club, though I demurred when the bartender slid the song request slips my way. A leather-faced hippie gave a slithery performance of a feline rockabilly number (“Stray Cat Strut”) rife with horny meows. A pock-marked lizard man in a flat brim and camo hoodie rapped a song I’d never heard from a 2004 album titled High Class White Trash: “I’m eatin’ Captain Crunch for lunch / Do I got issues? Yeah man, I got a bunch.” Two tall and deep-voiced cowboys, each in Stetsons and thick walrus mustaches, delivered a series of rambling road songs: Merle Haggard’s “Big City,” Bob Seger’s “Turn the Page,” and a lively rendition of Roger Miller’s “King of the Road”:

“Trailers for sale or rent

Rooms to let, 50 cents

No phone, no pool, no pets

I ain’t got no cigarettes…”

A cold wind blew through the patio at sunset, though nothing like the snowstorm that had hit the place last week. There’d been a flaming 32-car pile-up on I-40, or so Trina the bartender regaled me as we smoked. “There’s a family of three from Korea whose bodies they still can’t find. Last time their GPS pinged was just down Devil Dog Road.” “Hey man, look up there!” gasped the hippie rockabilly, pointing at the sky. “You see those clouds, how close they are together… Now watch how fast they move… See how different they look now?” And for a minute or two we watched the sky in wonder, out there in the mountain twilight.

Inside, an elderly woman known to the bar as “Mama” swayed on her bar stool as she yowled her shaky version of “I Think We’re Alone Now,” forgetting half the words. It was beautiful beyond belief. I swallowed my pride, filled out my request form, and to the cheers of cowboys, hippies, burnouts and bartenders, dutifully rocked the house to OMC’s “How Bizarre.”