“Is there a car rental place around here?”

“What?”

“Place to rent cars?”

“Ain’t seen any.”

“Uh… a train?”

“Oh. Now and then.”

— DON’T COME KNOCKING, 2006

The snack car opened in the Cascades at dawn, south of the Oregon border. The first in line wore nightclub loafers and ordered a microwave hamburger; as it warmed in its plastic he plundered the cooler, surfacing with two tall-boy Coronas which he added to his total with an air of whimsy: Well golly gee, fancy seeing these here! I paid for my coffee and watched from the observation lounge, where I’d spent a fitful night blasted by wet A/C, as Mount Shasta, just behind us now, turned pink from the tip down. Shrublands of bitterbrush and manzanita were overtaken by ribbons of lake, rose-gold and steaming as morning cracked the summit and settled now and then by silvery herons and tiny black ducks. I’d spent every hour since Friday on a train, or waiting to be — riding the Zephyr to its Pacific end, then transferring to the northbound Coast Starlight, where now it was Sunday.

“Gooooood morning from the dining car!” said a jazzy voice on the intercom. “We’ve been movin’ and groovin’, shakin’ and bakin’ since we opened at 6:30 this morning.” (Formal meals on long Amtrak rides are included for sleeping car passengers and sold at outrageous prices to everyone else; I caved only once to $25 lunch, ensorcelled by a loaded baked potato.) Quiet hours were over, and Mister Dos Coronas had begun to sing loudly in a language he seemed to be inventing on the fly, smacking a table for percussion. He now wore a towel on his head and waved his arms madly, reading the room, waiting for someone to stop him.

We drifted past a trailer park through which a lone cat jogged to some morning appointment, then sucked into the mouth of a black tunnel. Out the other end was Oregon, green like I’d never seen it before — green on a bender, off its meds. Upper Klamath Lake barely rippled as we hugged the shoreline, framed by the hazy peaks of young volcanoes, red-winged blackbirds running kamikaze trials, and an occasional stoic trout fisherman. “I ain’t about to get out in the middle of nowhere. I’ll get off when I know where I’m at,” hollered Dos Coronas to his phone. “I know where Chicago’s at. I’ll call you when I get to Chicago.” “Uh oh,” said my neighbor, who for hours had gently punished me with conversation on hydrothermal chemistry in geysers, the effect of cellphone towers on insect reproduction, and other such matters at hand.

The station stop in Chemult, Oregon (pop. 278) lasted no more than 80 seconds, long enough for a single passenger to disembark. Letting his half-open luggage tumble and spill about him, Coronas leaned against the railing, slid to the ground and raised, with trembling focus, a cigarette to his mouth. A conductor approached, exchanged a few words, shrugged, and disappeared inside as the Starlight let rip one woeful howl and pulled off towards Eugene, leaving the drunk man there. In the parking lot, a woman juggled bean bags, flinging them skyward and laughing as they fell.

Late afternoon I arrived in downtown Portland — as far as I could see, a ghost town but for several dozen tents and their murmuring inhabitants. It didn’t much matter. I had one night to kill before I boarded my third cross-country train in as many days: the Empire Builder, bound for Montana.

The sky was still dark when the Empire Builder slowed to deposit me at Libby Station Tuesday morning, though over the Kootenai River, past the Cabinet Mountains and Canada behind them, the blue had begun to pale. With my duffel on my back I headed south on Mineral Street, Libby’s downtown strip — Curves Fitness, Kootenai Thrift Outlet, Home Medical Oxygen, Mint Bar, no sign of action but for the florescence of a 24-hour laundromat, abandoned too. The sidewalk was sticky and the air sweet with Ponderosa pine sap. I turned at the old theater, whose marquee advertised one daily showing of John Wick 4, and walked along U.S. Route 2 for half a mile, where past the combination liquor store/casino buzzed the Country Inn’s VACANCY sign. I’d chosen this particular establishment based on advice from a Charles Portis novel: “I always try to get a room in a cheap motel with no restaurant that is a near a better motel where I can eat and drink.”

In the effort of searching for a clean, cheap room in Libby, Montana (pop. 2,903), one may find themselves, instead, with a page of links including an E.P.A. Superfund Site profile, a subsection of Asbestos.com, and a Guardian headline from 2009: “Welcome to Libby, Montana, the town that was poisoned.” Libby was a logging town along the Great Northern Railway until 1919, when vermiculite, a heat-resistant mineral useful for insulation, was found in the mountains. When W.R. Grace & Co. purchased the mine in 1963, it was producing 80% of the world’s vermiculite, a great source of local pride. As far back as the ‘70s, a federal trial would allege decades later, the company was aware that vermiculite was contaminated by an especially toxic form of asbestos, by that time present in the town’s air, the dirt, the dust, and the slag donated by W.R. Grace to local schools for running tracks, ice rinks, baseball pitches. By 2009, when the E.P.A. declared a public health emergency, calling it “the worst case of industrial poisoning of a whole community in U.S. history,” 200 of Libby’s 2,600 citizens had died of asbestos exposure and a thousand more were sick from it, some as young as 13. Today, it’s the only town in America with Medicare for All. New cases are still being uncovered.

This was not what brought me to the Country Inn Motel at six a.m. on a Tuesday. In fact it was a short book, Train Dreams by Denis Johnson, in which unfolds the haunted fictional life of the American laborer Robert Granier, who is eulogized towards the end like so: “Grainier himself lived more than eighty years, well into the 1960s. In his time he’d traveled west to within a few dozen miles of the Pacific, though he’d never seen the ocean itself, and as far east as the town of Libby, forty miles inside Montana. He’d had one lover — his wife, Gladys — owned one acre of property, two horses, and a wagon. He’d never been drunk. He’d never purchased a firearm or spoken into a telephone. He’d ridden on trains regularly, many times in automobiles, and once on an aircraft. During the last decade of his life he watched television whenever he was in town. He had no idea who his parents might have been, and he left no heirs behind him.”

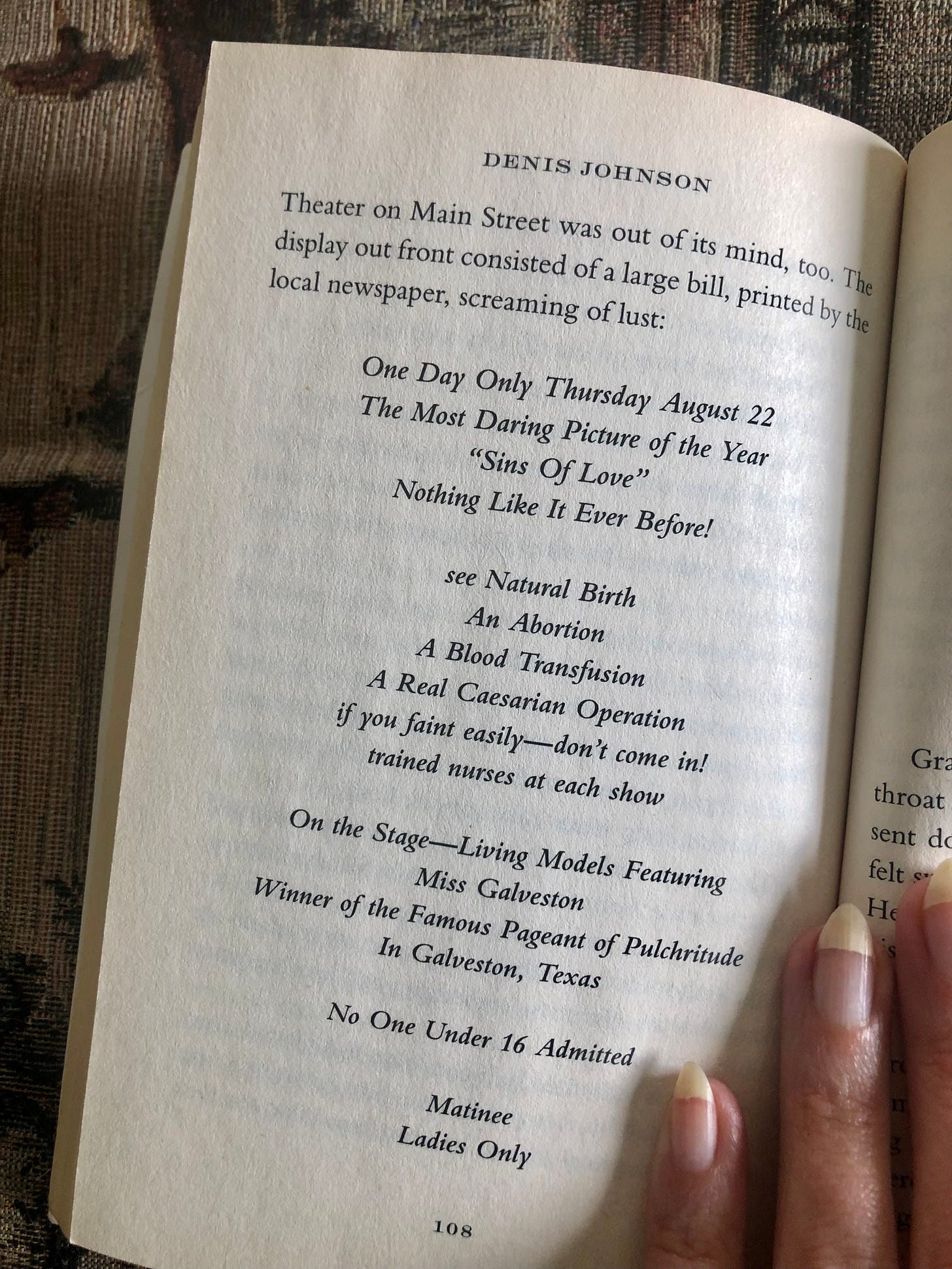

The orphan Robert Granier arrives in Northern Idaho by train, and in his youth, helps to transfigure the natural world of the American West, working for railroad companies to do away with portions of the forest and replace them with man-made structures of awesome magnitude. In 1920 he helps repair a massive railway bridge in Northwestern Washington and returns to the Idaho Panhandle to find that wildfire has ravaged the valley and his wife and infant daughter, along with his home, are gone. Granier then lives his remaining 40 years as a 21st century anomaly. He re-builds his cabin along the Kootenai River in the ashes of his former life, and lives there alone, or with a dog, where he howls along with wolves at night and occasionally encounters the surreal. He exists, peripherally to America’s industrial awakening, as one may have 100 years before — yet he has also stood outside a train which carried in it “the strange young hillbilly entertainer Elvis Presley,” and he has visited, lonely and addled with ambient lust, a county fair, where there is advertised a shocking film:

Back at his cabin, Granier is crazed by thoughts of this event — writhing in the grass, soaking in the frigid river, lying naked in the muggy nights, tormented all the while by dreams of Miss Galveston, Queen of Pulchritude in a darkened theater. He searches for the courage to arrive in town that day, and failing to find it, hikes frantically into the woods for miles on end, cursing his visions of sex and sin and pulchritude.

“At sunset, all progress stopped. He was standing on a cliff. He’d found a back way into a kind of arena enclosing a body of water called Spruce Lake, and now he looked down on it hundreds of feet below him, its flat surface as still and black as obsidian, engulfed in the shadow of surrounding cliffs, ringed with a double ring of evergreens and reflected evergreens. Beyond, he saw the Canadian Rockies still sunlit, snow-peaked, a hundred miles away, as if the earth were in the midst of its creation, the mountains taking their substance out of the clouds. He’d never seen so grand a prospect. The forests that filled his life were so thickly populous and so tall that generally they blocked him from seeing how far away the world was, but right now it seemed clear there were mountains enough for everybody to get his own. The curse had left him, and the contagion of his lust had drifted off and settled into one of those distant valleys.

He made his way carefully down among the boulders of the cliff, reaching the lakeside in darkness, and slept there curled up under a blanket he made out of spruce boughs, on a bed of spruce, exhausted and comfortable. He missed the display of pulchritude at the Rex that night, and never knew whether he’d saved himself or deprived himself.”

Presented here is an elegy for a life, and a way of life, that is gone forever and will never be again; you are free to conclude that civilization and its consequences have come at a disastrous cost, but Johnson leaves that one up to you. What lingers is the idea that even the most modest life, like Robert Granier’s, is suffused with awe and psychedelic mystery, brushing against the sublime every now and again. And here I was now in the heart of the Kootenai River Valley, not a mile from the rails of the train that whistled through the hermit’s dreams, checking into Room 103 at the humble Country Inn. Today I would hike the forest, across a swaying bridge dangling over the Kootenai Falls, leading me into the forgotten world…

“What’s the best way to get to the falls with no car?” I asked the woman working the front desk as she navigated the computer slowly, sipping a Rockstar can. She thought for a moment. “Well… there isn’t one.” “Oh! Maybe a taxi…?” “Sorry,” the lady said, not sounding especially so. “If you got a friend, you could ask them for a ride.”

I had a new plan. I would eat a pioneer’s breakfast, and after that, get drunk.

The Mint Bar opened at 6 a.m., “but we can’t sell booze ‘til 8,” the barback explained regretfully, as if this may have put a real hitch in my plans. To fill the two inexplicable hours, he liked to brew coffee for those coming or going on the once-daily 5:21 a.m. train, it usually running an hour behind schedule and the station being steps away. (I’d been one of two arrivals this morning, and tomorrow I’d find myself the only passenger at all.) Presently it was noon and the Mint was humming: ten people on bar stools, four shooting pool, twenty more silently fixed to electronic slot machines babbling their childish melodies. The bar was dim and wood-paneled, decorated with Christmas cards, funeral programs that curled at the corners, and placards advertising prison sentences for Hillary Clinton, lit by the women’s college softball game that played on three TVs. Shifting the toddler on her hip, a pretty sleeveless bartender poured me a Coors Light. Two dollars.

My habit of saying hello to passing strangers on the street had been met in Montana with diminishing returns. You do not hear much on the topic of the Treasure State’s famous hospitality, which is not to say its people are indifferent to their own. The problem here was me — an outsider, no way around it. Folks here didn’t wear Sambas, for one, and they certainly didn’t ask whether the NBA playoffs would eventually be shown. Conversation volleyed past me as newcomers were greeted with hugs, and dice skittered as people rolled their Shakes of the Day. Damn! I was the only adult in Montana without a driver’s license, and probably everyone could smell it. A 300-pound man, who had decided against pairing his overalls with an undershirt that morning, pulled up a seat and ordered a Jameson — “warm.”

“I couldn’t help but notice,” I said to the perspiring man, “that you ordered your Jameson warm.”

“Specialty of the house!” the man replied, and I watched as the bartender cupped his shot glass for 15 or so seconds, heating it in her palms. Well — this was a new one. I ordered the same. In minutes the man was showing off his only tattoo, the cover of Uriah Heep’s 1974 album Demons and Wizards — a masterpiece, had I not heard it — squeezed between meaty shoulder blades. I’d cracked the code. I was in!

The sun had yet to set when I made my stumbling return to the Country Inn, helping myself to a few unripe bananas from the all-day breakfast bar. Two girls, arms piled high with sheets and towels, gossiped as they passed. “The whole thing is, he believes that if you’re saved, you’re saved for life,” one whispered to the other. “But I believe that we have free will, and you can walk away from your salvation. That’s the only thing we disagree on.” In the brightness of Room 103, I slept like a stone.

The 5:21 a.m. eastbound Empire Builder was, as promised, exactly one hour late, enough time to sit outside the Mint Bar and share a coffee with the barback as the sky went pink over the mountains. To the south, above the river, a bald eagle seemed to levitate. A far-off whistle sounded and grew nearer, accompanied now by a doomsday roar. Metal shook the earth. The train slowed, a single door opened, and somebody called me by name.

This has been Part 4 of the Amtrak Chronicles on SCARY COOL SAD GOODBYE. For Part 3, click here. For Part 2, click here. Part 1, click here. Thanks for reading & God Bless America.